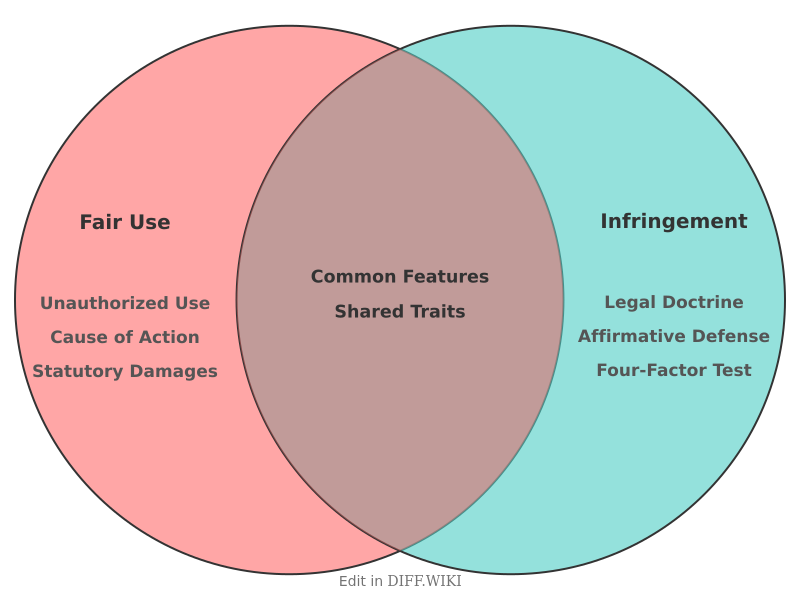

Differences between Fair Use and Infringement

Contents

Fair use vs. copyright infringement[edit]

Copyright law in the United States grants creators exclusive rights to their original works under Title 17 of the U.S. Code. These rights include the ability to reproduce, distribute, and perform the work. When a third party exercises these rights without the permission of the copyright holder, the act is classified as copyright infringement.[1] However, the law provides a limitation on these rights known as fair use. Fair use allows the public to use portions of copyrighted material for purposes such as criticism, news reporting, teaching, or research without seeking a license.[2]

The primary distinction between the two concepts is that infringement is a violation of law, while fair use is an affirmative defense used to excuse what would otherwise be considered infringement. In a legal dispute, the burden of proof initially rests on the copyright owner to show that their work was copied. If copying is established, the defendant may then argue that their specific use falls under the protections of fair use.

Comparison table[edit]

| Feature | Copyright infringement | Fair use |

|---|---|---|

| Legal definition | Unauthorized use of a copyrighted work that violates the owner's exclusive rights. | A legal doctrine that permits limited use of copyrighted material without permission. |

| Legal status | A cause of action for a civil or criminal lawsuit. | An affirmative defense against a claim of infringement. |

| Authorization | Occurs when use happens without a license or permission. | Permission is not required if the use meets statutory criteria. |

| Determination | Based on ownership of a valid copyright and copying of original elements. | Based on a four-factor balancing test defined in 17 U.S.C. § 107. |

| Intent | Generally irrelevant to the finding of liability, though it may affect damages. | The purpose and character of the use are central to the analysis. |

| Market effect | Usually results in a negative impact on the potential market for the work. | Use is less likely to be fair if it acts as a direct substitute for the original. |

| Financial outcome | May result in statutory damages, actual damages, or injunctions. | Results in no liability for the user if the defense is successful. |

Statutory factors of fair use[edit]

Courts determine whether a use is "fair" by evaluating four factors. No single factor is definitive, and judges weigh them together based on the facts of the case.

1. **Purpose and character of the use.** Courts look at whether the use is for commercial or nonprofit educational purposes. A key consideration is whether the use is transformative, meaning it adds new expression or meaning to the original, rather than merely replacing it.[3] 2. **Nature of the copyrighted work.** Uses of factual works, such as biographies or technical manuals, are more likely to be considered fair than uses of highly creative works like poems or films. 3. **Amount and substantiality of the portion used.** Taking a small excerpt is more likely to be fair use than taking the entire work. However, taking the "heart of the work" can weigh against fair use even if the portion is small.[4] 4. **Effect upon the potential market.** This factor examines whether the unauthorized use harms the copyright owner's ability to profit from their original work or derivatives.

Elements of infringement claims[edit]

To succeed in a claim of copyright infringement, a plaintiff must prove ownership of a valid copyright and that the defendant copied constituent elements of the work that are original.[5] Copying is often proven through evidence of "access" to the original work and "substantial similarity" between the original and the allegedly infringing version. If the similarity involves only unprotected ideas or facts, infringement has not occurred.