Differences between Nature and Nurture

Contents

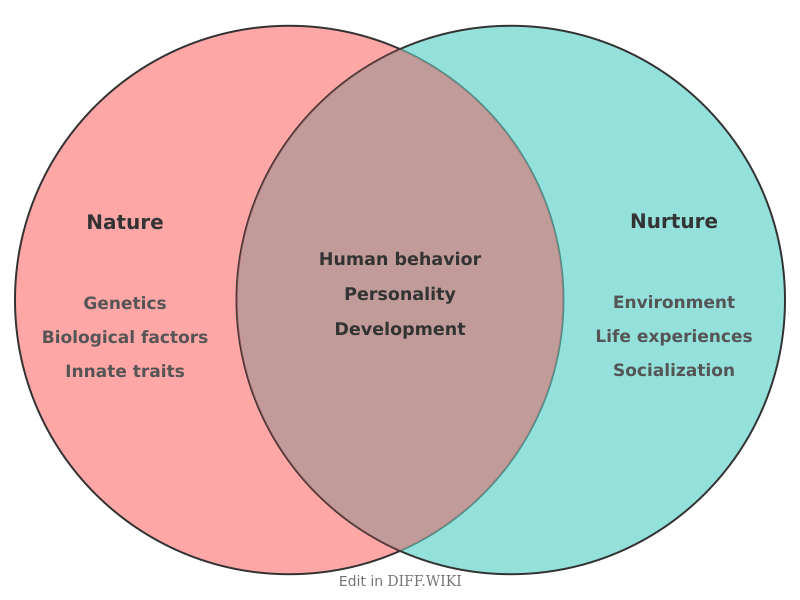

Nature vs. nurture

The nature versus nurture debate concerns the relative importance of an individual's innate qualities versus personal experiences in determining physical and behavioral traits. The phrase was popularized by the Victorian polymath Francis Galton in the 1870s, though the underlying philosophical inquiry dates back to classical antiquity.[1] Nature refers to biological and genetic inheritance, while nurture encompasses environmental factors, including upbringing, social relationships, and culture.

Modern scientific consensus has largely moved away from a binary view, instead focusing on how these two forces interact. This perspective, often called interactionism, suggests that genes and environment are not independent variables but rather work in tandem to shape human development.[2]

Comparison table

| Category | Nature | Nurture |

|---|---|---|

| Primary focus | Genetic inheritance and biological factors | Environmental influences and life experiences |

| Philosophical root | Biological determinism and nativism | Empiricism and the "tabula rasa" (blank slate) |

| Mechanism | DNA, hormones, and neurochemistry | Peer groups, education, and parenting styles |

| Examples of traits | Blood type, eye color, and certain genetic diseases | Language spoken, religious beliefs, and manners |

| Research methods | Twin studies and gene mapping | Observational studies and longitudinal case work |

| Developmental view | Maturation follows a biological timetable | Behavior is learned through conditioning and social mimicry |

| Key historical figures | Francis Galton, Konrad Lorenz | John Locke, B.F. Skinner, John Watson |

Historical perspectives

In the 17th century, philosopher John Locke proposed that the human mind at birth is a blank slate (tabula rasa), meaning all knowledge and traits result from experience. This view became a foundation for behaviorism in the early 20th century. Psychologists like John B. Watson argued that he could train any healthy infant to become any type of specialist, regardless of the child's ancestors or talents, by controlling their environment.[3]

Conversely, nativists argued that human characteristics are the product of evolution and that individual differences result from unique genetic codes. Early 20th-century eugenics movements relied on extreme interpretations of nature, suggesting that social standing and intelligence were entirely fixed at birth.

Behavioral genetics and interactionism

The use of twin studies has provided significant data for this debate. The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart found that identical twins separated at birth often shared similar personality traits, interests, and social attitudes, suggesting a strong genetic component for these characteristics.[4]

However, the field of epigenetics demonstrates that environmental factors can influence how genes are expressed. For example, a person may have a genetic predisposition for a specific health condition, but environmental factors such as diet or stress levels can determine whether the gene becomes active. This molecular-level interaction indicates that the two concepts are inextricably linked.[5]

References

- ↑ Galton, F. (1874). English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture. Macmillan and Co.

- ↑ Ridley, M. (2003). Nature Via Nurture: Genes, Experience, and What Makes Us Human. Fourth Estate.

- ↑ Watson, J. B. (1930). Behaviorism. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Bouchard, T. J., et al. (1990). "Sources of human psychological differences: The Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart". Science.

- ↑ Caspi, A., et al. (2002). "Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children". Science.