Differences between Fraunhofer Diffraction and Fresnel Diffraction

Contents

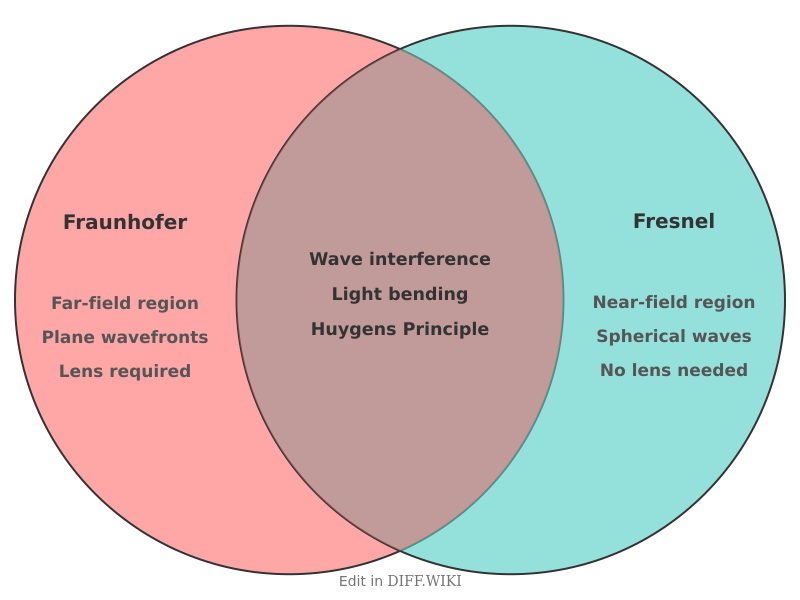

Fraunhofer diffraction vs. Fresnel diffraction

Diffraction is the bending of waves around the corners of an obstacle or through an aperture into the region of geometrical shadow. In optical physics, two distinct mathematical approximations are used to analyze these patterns: Fraunhofer diffraction and Fresnel diffraction. These models are distinguished by the distance between the diffracting object and the observation plane, which determines the curvature of the wavefronts involved.

Comparison Table

| Feature | Fraunhofer Diffraction | Fresnel Diffraction |

|---|---|---|

| Region | Far-field | Near-field |

| Wavefront type | Planar | Spherical or cylindrical |

| Distance | $L \gg a^2/\lambda$ (Infinite) | $L \approx a^2/\lambda$ (Finite) |

| Fresnel Number ($F$) | $F \ll 1$ | $F \geq 1$ |

| Mathematical Tool | Fourier transform | Fresnel integrals |

| Optical elements | Often requires lenses | Lenses are not required |

| Pattern behavior | Pattern size changes with distance, but shape remains constant | Pattern shape and size change with distance |

Physical Principles

Fraunhofer diffraction occurs when the light source and the observation screen are effectively at an infinite distance from the aperture. This condition ensures that the waves reaching the aperture are plane waves, and the rays reaching any point on the screen are parallel. In laboratory settings, this "far-field" condition is often simulated by placing a converging lens between the aperture and the screen. The lens maps parallel rays to a single point in its focal plane, allowing the far-field pattern to be observed at a finite distance. The intensity distribution in Fraunhofer diffraction is proportional to the squared magnitude of the Fourier transform of the aperture function.

Fresnel diffraction, or "near-field" diffraction, describes patterns formed when the source or the screen is close to the aperture. In this regime, the wavefronts retain their curvature—either spherical or cylindrical—as they pass through the opening. Unlike the far-field case, the diffraction pattern in the near-field changes significantly as the observer moves along the optical axis. Calculation of these patterns requires Fresnel integrals, which account for the phase differences resulting from varying path lengths between different parts of the aperture and the observation point.

Transition Between Regimes

The transition from Fresnel to Fraunhofer diffraction is defined by the dimensionless Fresnel number ($F$). This value is calculated using the formula:

$F = \frac{a^2}{L\lambda}$

In this equation, $a$ is the characteristic size (such as the radius) of the aperture, $L$ is the distance from the aperture to the screen, and $\lambda$ is the wavelength of the light. When the distance $L$ is large enough that $F$ is much less than 1, the Fraunhofer approximation becomes valid. When $L$ is small and $F$ is 1 or greater, the Fresnel model must be used to maintain accuracy.

References

- ↑ Hecht, Eugene (2017). Optics (5th ed.). Pearson Education. pp. 457–510. ISBN 978-0133977226.

- ↑ Goodman, Joseph W. (2005). Introduction to Fourier Optics (3rd ed.). Roberts and Company Publishers. pp. 63–75. ISBN 978-0974707723.

- ↑ Born, Max; Wolf, Emil (1999). Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference and Diffraction of Light (7th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 412–450. ISBN 978-0521642224.