Differences between Jogging and Running

Contents

Jogging vs. running[edit]

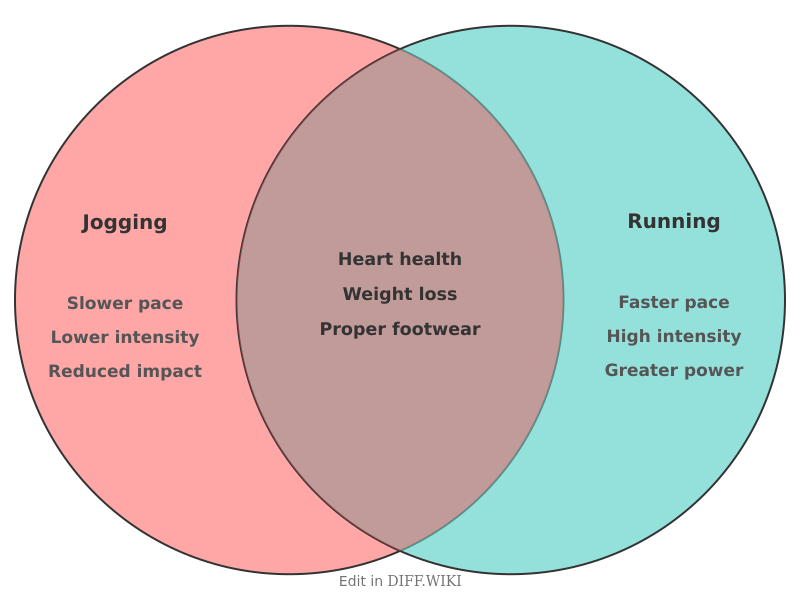

Jogging and running are forms of aerobic exercise characterized by a gait where both feet are briefly off the ground simultaneously. The distinction between the two activities is primarily based on speed, biomechanical intensity, and metabolic demand. While the terms are often used interchangeably in casual conversation, sports scientists and athletic coaches apply specific criteria to differentiate them.

The most common threshold for distinguishing jogging from running is a speed of 6 miles per hour (9.7 km/h), or a 10-minute mile pace. Movement slower than this limit is classified as jogging, whereas movement faster than this limit is defined as running.

Comparison table[edit]

| Category | Jogging | Running |

|---|---|---|

| Speed threshold | Slower than 6 mph (9.7 km/h) | Faster than 6 mph (9.7 km/h) |

| Gait pattern | Shorter stride; more vertical bounce | Longer stride; greater forward propulsion |

| Flight phase | Brief period of suspension | Extended period of suspension |

| Oxygen consumption | Lower VO2 demand | Higher VO2 demand |

| Caloric burn | Approx. 100 calories per mile | Approx. 120–150+ calories per mile |

| Joint impact | Lower ground reaction forces | Higher ground reaction forces |

| Muscle recruitment | Primary focus on calves and glutes | Increased engagement of hamstrings and core |

| Primary energy system | Aerobic | Aerobic and anaerobic (at high intensities) |

Biomechanics and gait[edit]

The biomechanical differences between jogging and running relate to the "flight phase"—the interval during a stride when neither foot is in contact with the ground. In running, this flight phase is more pronounced. Runners use their arms more aggressively to maintain balance and generate momentum, often keeping elbows at a strict 90-degree angle.

Joggers typically exhibit a shorter stride length and a higher degree of vertical oscillation, commonly referred to as "bouncing." This movement style results in lower ground reaction forces compared to running. Research published in the journal Sports Medicine indicates that runners experience impact forces between 2.5 and 3 times their body weight with each step, whereas joggers experience forces closer to 1.5 to 2 times their body weight [1].

Physiological and metabolic effects[edit]

Both activities improve cardiovascular health, but they place different demands on the body's metabolic systems. Running requires more energy per minute because the body must lift its entire mass off the ground more forcefully and more frequently. According to the American Council on Exercise, a person weighing 150 pounds (68 kg) burns approximately 132 calories during a 10-minute run at 6 mph, while the same person would burn fewer calories walking or jogging at a slower pace [2].

Heart rate zones also differ. Jogging generally keeps the heart rate within 60% to 70% of its maximum, a zone often used for fat oxidation and basic endurance building. Running typically pushes the heart rate into the 70% to 90% range, which improves aerobic capacity and increases the afterburn effect, known as excess post-exercise oxygen consumption (EPOC).

Historical context[edit]

The modern popularity of jogging as a planned exercise regimen began in the mid-1960s. New Zealand coach Arthur Lydiard is credited with developing the concept as a social and health-oriented activity. The practice was later popularized in the United States by Bill Bowerman, co-founder of Nike, following a trip to New Zealand. Bowerman published the book Jogging in 1967, which established the first formal guidelines for the activity for the general public [3]. Prior to this period, running was almost exclusively associated with competitive athletes and military training.